Here are some preliminary thoughts on obsession and enchantment:

1) Vladimir Nabokov, in his autobiography Speak, Memory, referred to Lolita as (to paraphrase) a long and painful birth. No doubt there was inspiration for the characters, and we even get a hint to a girl Nabokov met in the Crimea that might been the seed for the pederast Humbert's own obsession.

To speak nothing of Nabokov's own obsession, does Lolita, for the author and Humbert, qualify as an enchanter? I don't think so.

|

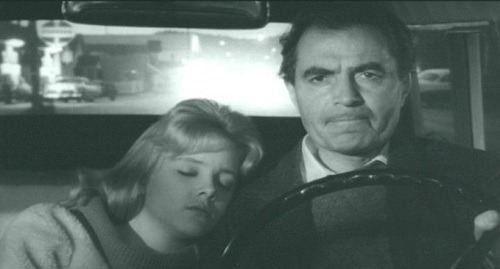

| James Mason as Humbert Humbert in Stanley Kubrick's Lolita (1962) |

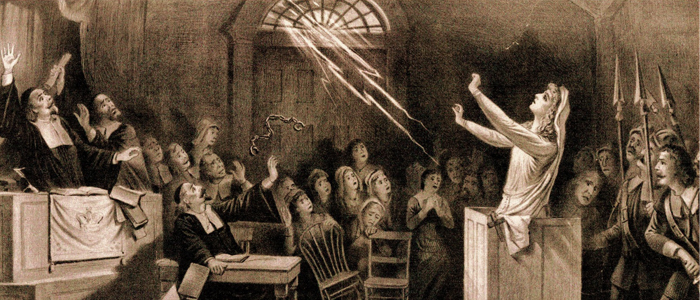

2a) Consider our enchanted Salem. The spell casters were external: Tituba and Goody Martin, only to name two. There were many more besides: almost anyone can cast a spell, can cause the enchantment to occur. The afflicted girls, the hallucinations of John Kembal, these were enchantments. They were cast by the incantation, brought externally into the internal workings ("afflictions") of the enchanted. Soon all of Salem was enchanted. It exceeded itself, it even found itself "afflicted" or "possessed." I would even say to some extent obsession became evident. Obsession, perhaps, was found in the religious leaders. We might be able to argue that Cotton Mather became obsessed by this, since he viewed all from a distance, his incantation might have been driven by himself. This is merely conjecture.

3) Dick Hugo: "We create our prisons and we earn parole each poem." (Letter to Birch from Deer Lodge)

4) In my dream, it wasn't the spirit of my friend calling to say you've forgotten about x and y, it was my own mind signalling to me. That is the creation by the self, the incantation of the self, the spell cast on the self. Poetry, too, can be like this, although I see some elementary dichotomies at play here.

4a) The enchanted/obsessed binary is linked to the binary set out by Lorca: the Muse and Duende. The muse is external to the poet, the sublime speaking into the poet's ear, the poet an enchanted vessel. The Duende is a demon-spirit, housed in the bowels of the poet, rising up out of the poet's own unconscious, being vomited forward. The Duende is a creation of the self, not always such a darkness as I have painted it, but a being that doesn't hold the heavenly or sublime light of the Muse and the Angel.

4b) The poet struck by the Muse is often found in address: the apostrophe is in use. "Sing to me, O muse" is the daily prayer of this poet. Not to say all poems that lack the expressive "O" are without the muse. Whitman's poem in the last segment shows the enchanted, in this case the Astronomer and the stars are the expressive "O," they are the external force.

4c) Likewise, the address can be made without realization that the obsessed is addressing himself. Consider Humbert's first spell-casting:

"Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta. The tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta." (Nabokov)

Here is Humbert's incantation, to himself. The Lolita which has a self is lost in the mouth of Humbert's incantation, becomes broken into pieces of sound. It is not Lolita who makes the incantation: she is Humbert's self-incantation. She does not enchant: he is already enchanted. It is a self enchantment: it is an obsession.

4d) To take another example of a character obsessed: who does Eliot's Prufrock really address if not himself -- or the self in visage? Prufrock enchants himself firstly, and then proceeds to enchant the rest of us; even Eliot is not immune. Prufrock is born of Eliot's mind, an obsessed Self actualized.

4e) With Humbert and Prufrock: they can and do enchant us. That is what the obsessed poet accomplishes. If the enchanted poet is able to spread the Word, the obsessed poet manages to spread the self. We actualize, we play accomplice.

5) I knew a boy of seventeen, who fell deeply in love with a girl the same age. They were both young and new to experience, but the girl had a better grasp on the realities of the world than the boy had. She had been visited by a demon, we'll call it Loss, early in life, when her parents had divorced. So the demon Loss was not a new thing in her life, and, like a second child, when each new Loss came they all became easier to carry.

Everyone carries Loss around, sometimes many Losses. Sometimes the burden of Loss can be too much. Most of us manage to find a way to let it sit inside us without it bothering us too much. A new Loss comes around and we manage to shift the other Losses around so as to make more room. Sometimes a particular Loss just leaves, and we come to forget its face, and we wonder what we were so upset with in the first place.

When the boy and girl were twenty, the girl broke things off, and the boy bore the first Loss he had had to deal with. And the boy tucked away that Loss, let it nest in his heart. He took Loss hard, is what I mean to say. Loss breathed fire into his ventricles and arteries until the breath of Loss tingled down every nerve in his body. It was wholly pathetic to watch.

Why this anecdote is particular is that the boy had been enchanted with the girl, but when the girl left she did not leave by still enchanting; instead, the boy allowed himself to be enchanted with his own Loss. This was obsession. This is the obsession of love unrequited: it is not the beloved, but the lover, the lover enchanted with the idea of Love or the idea of Loss, each one equally within the self enchanted.

That Loss that came from the girl eventually grew old and died. The boy also became older, learned to hold greater Losses at greater distances. Deaths of friends and family made the First Loss go to seed. It isn't that the First Loss is gone, for it could sprout from some organ of the boy at any time. For now, it lays buried, with a hard frost atop it.