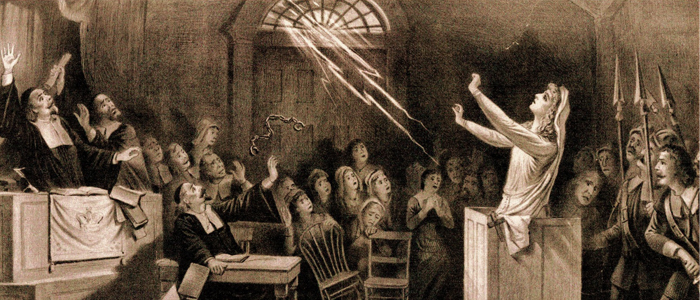

Marion Starkey tells us that the Salem witch trials began due to the tendency of girls in Puritan culture--girls on the verge of adulthood, who were, in Starkey's words were "without Puck"; and could not find relief, especially in winter, for their energies and imaginations--that these girls were, essentially, bored. Their angst had not the outlet we have today: to scream out of fast moving car windows, to dance, et cetera. In lieu of any avenue for imaginative retreat (which was repressed out of society, in the sense that most other books and stories were falsehoods and therefore in the Devil's domain), Abigail Williams (only eleven, whatever Miller writes) and the rest of the girls found a new sanctuary in the stories and ju-ju of Tituba, who spent all winter weaving tales and incantations across and around them.

|

| This scene is as much an internal creation as it is an external force. |

Likewise, when the region came to be possessed with what can only be described as Lust in condemning witches, it was not the afflicted girls who enchanted, but rather the townspeople's own conscious and unconscious behaviors. The town began to create a reality, possessed with the imaginative spirit of Lucifer first (and God, ironically, only secondary, in that it was God's work to capture and kill any witch in their midst), and the reality was autonomous to any real enchanter. It cannot be blamed of the girls entirely that the judges condemned the witch, just like it cannot be blamed on the witch that the girls were able to create such real harm to themselves, pain that they truly believed in.

Puritan Massachusetts fell into chaos. Witches were found in all corners of the villages. A woman walking past one of the afflicted might cause for no reason she could see real harm to the afflicted girl. But the witch did not do the harm: it was the girl's imagination. Once the incantation takes place, it is only upon the enchanted to continue the spell, which is a kind of a metaphysical reinterpretation of Eleanor Roosevelt's famous quote, "no one can make you feel in inferior without your consent." And there were choices involved, to the self-enchanted. As much as the world seemed to be full of external forces, it was instead internal creation and imagination.

In poetry, then, the incantation releases the poem, the craft, into the waters of the imagination. But it is the reader or reciter of poetry who allows that poem to grow. In this sense, I can think of poem after poem that has lingered in my head without stop, entirely enchanting me but of my own enchantment. To another, it would appear boring, it would not have the effect. But this type of enchantment does recall to mind a poem by Walt Whitman:

When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer.

When I heard the learn'd astronomer ;

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me ;

When I was shown the charts and the diagrams, to add divide,

and measure them ;

When I, sitting, heard the astronomer, where he lectured with

much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon, unaccountable, I became tired and sick ;

Till rising and gliding out, I wander'd off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time

Look'd up in perfect silence at the stars.

The simplicity of meaning, almost an insurrectionary impulse in the speaker to resist science for the sublimity of the natural world, is complicated by the fact that the speaker had nevertheless "heard the learn'd astronomer." The words had been spoken, and spoken again, into the poem. The enchantment is upon the speaker, and is the speaker's enchantment, the astronomer's lecture. The lecture reprints itself onto the night sky. The silence of the stars includes the lecture of the astronomer. There is no separating the two. And it is not the astronomer that enchants the night sky, but rather the enchanted, writing the lecture into the sky.

In Whitman's poem, the external forces may seem to be the Astronomer and Nature. But Whitman internalizes both, by making them equal subjects of the poem. They are projected out in an act of creation, harmless of course (not at all as dangerous as Abigail Williams' projections) because they have enchanted, and the enchanter must act. The poet is always the enchanted object trying to release the spell from himself.

No comments:

Post a Comment